By Akane Otani

Want to work on Wall Street? Suit up, turn your spell check on, and leave your risk-taking, self-starter attitude home.

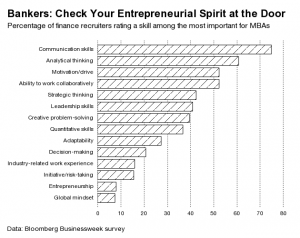

When finance industry professionals that interview new MBAs were asked to identify skills they deemed most important in applicants, 75 percent picked communication skills, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek survey of 1,320 recruiters conducted as part of our 2014 MBA rankings (including 212 from financial services, banking, and accounting companies). Recruiters also prized analytical thinking (which 60.8 percent said was highly important), motivation and drive (52.4 percent), and the ability to work collaboratively (also 52.4 percent). Those surveyed could name up to five skills, so the numbers don’t add up to 100 percent.

A track record of cross-cultural fluency or an ability to create initiatives from scratch, however, were the skills least valued by finance recruiters. While these attributes are low priorities for the entire group of MBA recruiters surveyed, finance people rate them even lower: Some 7.5 percent said a global mindset was an asset, compared to 12.3 percent of all recruiters, and 8 percent said being entrepreneurial was important, compared to 8.9 percent of all recruiters. Headhunters weren’t too fond of risk-takers, either. Just 15.6 percent of finance recruiters gave high ratings to taking initiative and risk , compared to 16.1 percent of all recruiters.

It may seem odd to see an adventurous, lone-wolf attitude rated poorly by Wall Street headhunters. After all, isn’t a certain amount of risk necessary to reap financial rewards? Don’t hiring managers want job applicants they can picture charging into boardrooms with radical proposals to invent the next financial instrument?

Actually, they don’t.

“Wall Street’s been under a lot of pressure for having too many people with a risk-taking mentality,” says Scott Rostan, chief executive officer of Training the Street, a New York-based firm that trains junior bankers and business school students. “So it doesn’t surprise me that in this regulatory environment, they want someone who’s going to follow the lead instead of going out on their own.”

Most newly-minted MBAs become investment banking associates—not the decision-makers in the middle of an important new deal. Associates need strong communication skills to understand what upper management wants out of a PowerPoint deck. They need to be able to work collaboratively to get projects done. What they don’t need is original ideas.

“I see a lot of ex-military members who serve this country, go on to business school, and do extremely well on Wall Street because they get it,” Rostan says. Investment banks, Rostan says, have a military-style hierarchy—with the managing directors being the generals, vice presidents being the captains, and analysts and associates being the privates and sergeants. Those who like structure are poised for success. On the other hand, those searching for more flat workplaces might hate Wall Street. “I’ve seen lots of people who are very bright and open and creative who haven’t done that well,” Rostan says. “They’re told to go left, and they want to go right.”

What options are left, then, for an associate who can’t contain his or her risk-taking, entrepreneurial ways? Why, pack up and leave for the startup world. At Harvard Business School, the share of MBAs taking jobs in the tech industry rose to 17 percent in 2014, from 10 percent over the last five years; at Wharton, that number rose to 13.7 percent, from 5.6 percent over the same period.

“Smart, talented people, whether they’re MBAs or undergrads, are going to want to follow the best personal opportunity for them,” Rostan says. “Going to a smaller company could be very attractive to some people with the personality for it.”