What is meant by Enterprise Value?

A simple way to think about enterprise value is that it represents the market value of all the assets of the firm, regardless of how they are funded. In contrast, equity value refers to only the common equity holders’ residual stake in the value of the firm’s assets.

However, when used for discounted cash flow or comparables, a company’s enterprise value would only reflect the cash-flow generating, operating assets of the firm. In other words, any asset that does not generate EBITDA would not be included in enterprise value. This exclusion is performed so that values can be compared when performing valuation analysis. For example, cash on hand does not generate any EBITDA (rather it generates interest income which is recorded lower down in the income statement), so therefore it should not be included in EBITDA. Similarly, any unconsolidated assets (such as Equity Method or other Long-term Investments) would not be included.

This does not mean that we ignore the value of these non-EBITDA generating assets when valuing a company. Rather, the value of these assets gets captured when using enterprise value to then calculate the equity value of the firm.

Why do investment bankers like Enterprise Value?

Enterprise value provides a true sense of the size and scale of a company since it includes the value of all the company’s operating assets, regardless of how they are financed. By contrast, equity value only measures the portion of the asset value accruing to the equity holders of a company. So, using enterprise value facilitates size comparisons as well as valuation analysis.

Using enterprise value as a basis for comparison separates the valuation decision from the financing decision. For example, this is how people evaluate residential real estate. They look at the enterprise value of the house or condo (i.e. the price in the market). Then, separately, they evaluate the financing decision which involves a down payment (equity) and arranging a suitable mortgage (debt). They are able to value the investment separately from their decision on how to finance the purchase.

In the world of Finance, all tasks come down to two major questions:

- How much is an asset worth?; and

- How should that asset be financed?

Enterprise Values allow finance professionals to focus on how much an asset is worth without worrying about how it is currently financed.

When do we use Enterprise Value in ratios?

Enterprise value is used in ratios for two primary purposes: (i) valuation and (ii) credit assessment.

A common valuation multiple using enterprise value is EV / EBITDA. Since EV is a measure of the company’s assets, it makes sense to compare EV to the company’s EBITDA which represents a measure of profits attributable to all capital providers. Thus, the ratio of EV / EBITDA is consistent in that all capital providers are represented in both the numerator and the denominator. However, as mentioned earlier, it is critical that any non-EBITDA generating assets be excluded from enterprise value so as not to distort the multiples.

Lenders use enterprise values to understand what proportion of the firm’s assets are funded with debt. A common ratio (especially for more highly leveraged companies) is Total Debt / EV. Since enterprise value represents the market value of the assets, this ratio gives a meaningful picture of how risky the company’s debt position is.

What is EBITDA? Why do investment bankers use it and how do we calculate it?

EBITDA stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. It is used by the investment banking / corporate finance community since it is a measure of profit that is available to all capital providers and is comparable to a company’s EV for the reasons noted above. We can calculate EBITDA by starting with revenue, subtracting the cost of goods sold (COGS) and subtracting the selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expenses according to the equation below:

EBITDA = Revenue – COGS – SG&A (excluding depreciation and amortization)

It is important to understand where depreciation and amortization (D&A) sit on the company’s income statement. For some companies, D&A is embedded in COGS and/or SG&A, so D&A needs to be added back separately to arrive at EBITDA – the D&A can be found in the operating section of the cash flow statement.

EBITDA is also a close proxy for cash flow which is another reason why it is helpful for those in the investment banking community. However, EBITDA does not take into account taxes, depreciation or amortization. These items can be significant since each company may have a completely different tax situation. Also, depending on the age of the assets that each company owns, they may have vastly different Capex profiles and depreciation amounts. Finally, EBITDA does not take into account a company’s changes in working capital which can also change significantly over certain periods of time.

Ultimately, EBITDA is used extensively in the finance industry because it is simple and easy to calculate, but analysts should be mindful that two companies with similar EBITDA may have very different cash flows because of the items described above. They therefore may trade at very different EBITDA multiples because investors will factor in the differences when pricing the stock.

How do you calculate Enterprise Value?

Since enterprise value is the value of all the company’s operating assets, one might think it could be calculated by individually valuing each asset on a company’s balance sheet. However, this is usually not possible because companies do not typically disclose the market values of their assets. It is more common to calculate a company’s enterprise value by adding up the market value of all of the capital that is funding the company’s assets. In other words, investors in all of the capital (i.e. debt, common equity, preferred shares) of the firm expect to share in the value of the assets, so it follows that the total value of all the capital equals the value of the assets.

The basic formula for EV is:

EV = Market Capitalization + Total Debt + Preferred Shares – Cash & Equivalents

The market capitalization is calculated by multiplying the most recent share price times the fully diluted shares outstanding (see the section entitled “Fully Diluted Shares Outstanding”).

Of note, cash & equivalents are deducted from the calculation above because they are not operating assets and they do not generate EBITDA (we described EV earlier as the cash-flow generating operating assets of the business).

Additional adjustments may need to be made to the EV calculation if the company has non-controlling interests or long-term investments (including equity method investments). These are covered in later questions.

What do you include when calculating the total debt number?

Any debt that is interest-bearing (i.e. money has been lent to the company with an expectation of return) should be included. All amounts of long-term and short-term debt should be included, including current portion of long-term debt. This includes drawn revolvers, bank loans, bonds, debentures, notes etc.

Capital leases should be included in the debt number as well since capital leases are effectively debt on unique assets. For credit analysis, it may be necessary to treat operating leases as if they are capitalized (ask your team). However, this will become a moot point as accounting rules will soon force companies to treat all leases as capital leases. This means that there will be an explicit lease liability on the balance sheet that can be added to total debt.

If the company has convertible debt, treat this as debt in the EV calculation to the extent the security is not in the money – if it is in the money, it should be assumed to be converted into common shares and included in the market capitalization calculation. Make sure these amounts are not double-counted.

Payables of any type should not be included in total debt. Payables are liabilities, but they are not debt since they do not bear interest. The undrawn portion of a revolving line of credit should also not be included in the total debt since it is not borrowed money – only the drawn portion of a revolver should be included (the drawn portion is the amount that would be recorded on the balance sheet).

How do we calculate the value of debt and preferred shares?

When calculating enterprise value, most professionals typically prefer to use market values for all components of the capital structure in order to obtain an accurate proxy for the market value of the company’s operating assets. While it is easy to get the market value of the common equity (for a publicly-traded company), it can be more difficult to get market values for preferred shares and debt.

Since preferred shares often do not trade publicly, the book value will usually be sufficient. However, check to see if the preferred share trade on an exchange.

This issue is similar for debt. Bank debt does not trade in a liquid market, so book value is almost always used. Some corporate bonds / notes do trade, so it may be possible to obtain market values.

For healthy companies, the book values for preferred shares and debt will usually be very close to the market values. So, in many cases, book value will simply be used as a proxy for market value. However, one should be cautious when using book values for a distressed company since market values of the debt will almost certainly be considerably lower than the book values.

Ultimately, when doing comparables analysis, it’s important to be consistent amongst all companies in the comp set and read each company’s disclosure to look for potential issues with their debt.

Should a pension liability be included in the calculation of Enterprise Value?

In most instances, we would not add a pension liability to a company’s enterprise value calculation. However, in some cases, it may be appropriate to add a company’s pension liability when calculating their enterprise value. If a company’s pension plan is a defined benefit plan and the plan is significantly underfunded, (i.e. the value of the pension plan assets is significantly lower than the pension liability), the company may need to issue debt to top up the plan. However, an underfunded pension plan can reverse itself quickly if the value of the plan assets recovers in the future.

Making an adjustment to EV to reflect pension liabilities is very subjective. Theoretically, the value of the operating assets should not change because of a pension obligation – rather, if the equity holders think there are new significant top up payments to be made, the value of the equity should drop (i.e. a greater portion of the value of the operating assets is now attributable to the debt holders). Therefore, to make EV comparable across companies, one should only add back the pension deficit (or some portion of it) if one believes the company’s share price has been impaired to reflect the pension issue.

What is net debt?

Net debt is defined as total debt minus cash & equivalents. Net debt is a metric often used by lenders since a company could use its cash resources to pay back debt. Thus, net debt is a measure of how much debt a company would have if it used its cash to reduce the amount of debt. However, this is not really the rationale for subtracting cash in the EV calculation. Rather, as mentioned in an earlier question, cash is deducted because it is not an EBITDA-generating operating asset.

Why do we add noncontrolling interest to a company’s Enterprise Value?

If a parent company owns between 50+% to 80% of a subsidiary, it will likely use the consolidation method to report the results of that entity – in other words all the revenues, expenses, assets and liabilities of the controlled subsidiary will be fully consolidated on the parent’s financial statements, even though the parent owns less than 100%. The remaining stake will be reported as noncontrolling interest (NCI) on the parent’s books.

It may seem counter-intuitive to then add the NCI to EV since it is the portion that the parent does NOT own. However, when we calculate EV, we need to include 100% of all the operating assets that the company consolidates – we therefore need to include the funding for the minority stake in the consolidated, but non-wholly owned assets (i.e. the NCI). Think of NCI as just another form of capital (in this case, third party equity instead of common or preferred equity or debt) funding the consolidated operating assets. We most often calculate EVs to make them comparable to other companies, so it makes sense to treat all companies the same with respect to accounting principles.

Another reason for adding NCI when calculating EV is to ensure comparability when calculating EV / EBITDA ratios. Since the parent consolidates subsidiaries for which it owns more than 50%, the parent will include 100% of the EBITDA from the subsidiary in its consolidated EBITDA. Without an NCI adjustment to EV, the EV will include only the portion of the equity value of the subsidiary that’s owned by the parent (since that’s what is reflected in the parent’s market capitalization) and 100% of the subsidiary’s debt (since it is consolidated on the parent’s balance sheet. Thus, to make the EV and EBITDA comparable (i.e. the same collection of assets), we must add the NCI to the EV. (See the section entitled “Noncontrolling Interest”.)

Why don’t we just subtract some of the parent company’s EBITDA to get a consistent EV / EBITDA ratio?

Adjusting the 100% EBITDA contribution in the denominator can be difficult if the parent company does not disclose the EBITDA for the subsidiary. Thus, the numerator (EV) is usually adjusted by adding back the NCI. This makes the numerator and denominator comparable by setting them both to 100%. Also, the parent company controls the subsidiary. Thus, it is prudent to have the numerator and denominator at 100% since the parent is controlling the subsidiary. The other issue with reducing the denominator is that a portion of the subsidiary’s debt would also need to be removed from the debt of the parent company. Since the debt amounts on the parent company’s balance sheet are consolidated, the subsidiary’s debt amounts may not be disclosed (check the debt footnote to see if the segmented debt is disclosed).

Where can we find the NCI amount?

The NCI amount will be shown on the parent company’s balance sheet. If the parent has a controlling interest in a number of subsidiaries, the NCI shown on its balance sheet will reflect the combined NCI in all of these subsidiaries. The only problem is that the NCI on the parent’s balance sheet is the book value of the NCI – ideally, we want the market value of the NCI to be consistent. We mentioned earlier that we want the market values of all the pieces of capital. The share of the controlled subsidiary owned by the parent will be priced into the parent’s equity value at the assumed market value.

If the subsidiary is a public company (i.e. some or all of the shares held by the NCI is publicly traded), then it makes sense to use the public share price of the subsidiary to calculate the NCI for the EV. The NCI would equal:

Market value of NCI = share price of subsidiary * shares owned by NCI shareholders

However, more often than not, NCI relates to privately-held subsidiaries. In this case, you may have to rely on the book value of the NCI, although this is not ideal since the market value could be very different from the book value. If the NCI is significant (perhaps the subsidiary is large relative to the parent), it could make sense to value the NCI using a multiple method. To do this, find an acceptable valuation multiple for the subsidiary and then calculate the resulting value of the NCI equity stake. If you use an EBITDA multiple, make sure to deduct the subsidiary’s net debt and preferred shares before calculating the value of the NCI equity.

Would you ever calculate enterprise value without adding in NCI?

When calculating enterprise value to use in an EV / EBITDA multiple, NCI would always be included. It is added to the numerator to eliminate the mismatch between the numerator and the denominator. However, in a merger or an acquisition, the NCI would not be added to the enterprise value. In this case, the enterprise value of the target company is calculated without the NCI since the acquiring company would not have to pay for the NCI. The acquiring company does not have to pay for the NCI since the NCI is the portion of the subsidiary which the parent company does not own.

Why do we deduct long-term investments when calculating enterprise value?

If a parent company owns 50% or less of another company and does not control the operations of the subsidiary, typically the subsidiary’s results will not be consolidated into the parent’s financials. Depending on the ownership level, the parent may use the Equity Method of accounting or it may simply account for the stake as an investment on the balance sheet. In either case, the stake would be categorized as a long-term investment (LTI).

When calculating the EV of the parent, LTI is subtracted from the total. The idea is similar to the rationale for adding NCI to EV, but in this case it’s the reverse. Theoretically, the value of any LTIs have already been priced into the parent’s share price and market capitalization using investors’ best assessment of the fair value of these assets. But to make the parent’s EV comparable to those of other companies, we need to remove these assets. Because the LTIs are not consolidated, they are not part of the parent’s “operating” assets and do not generate EBITDA.

As previously mentioned, to make a multiple (such as EV / EBITDA) comparable, the same collection of assets must be in the numerator as well as in the denominator. Suppose the parent has a 30% equity stake in another company (since they use the equity method, the investee company would not be consolidated). Without any adjustment to EV for the LTI, the EV would include the value of the 30% stake (since the stock market prices it into the stock price) but the EBITDA would have no contribution from those assets. So, we have a mismatch with 30% of the value of the investment in the parent’s EV, but 0% of the investment’s EBITDA in the denominator. To correct this, we remove the value of the 30% stake from the EV of the parent.

Importantly, this does not mean we are ignoring the value of the 30% stake. Rather, we would include the value of any LTIs (or other non-operating assets such as cash) in the equity value calculation.

Would you ever calculate enterprise value without deducting LTIs?

In some situations in credit analysis, it may make sense to leave the LTIs as part of EV. For example, in a Debt / Total Value ratio, it could make sense to include the LTI in the denominator since they are a potential source of support / liquidity to repay the debt. The important thing is to be consistent across companies and clearly label your work.

Where can we find the LTI amount?

It is always best to use market values for all components of an enterprise value calculation. If you know the value of the LTI is immaterial, it may be sufficient to use book value. However, where components of the LTIs are publicly-traded, use the share price times the # of shares owned by the parent. If the LTI is material but private, it might make sense to try to use a multiple to estimate the value of the investment.

How do you go from a company’s Enterprise Value to its Equity Value?

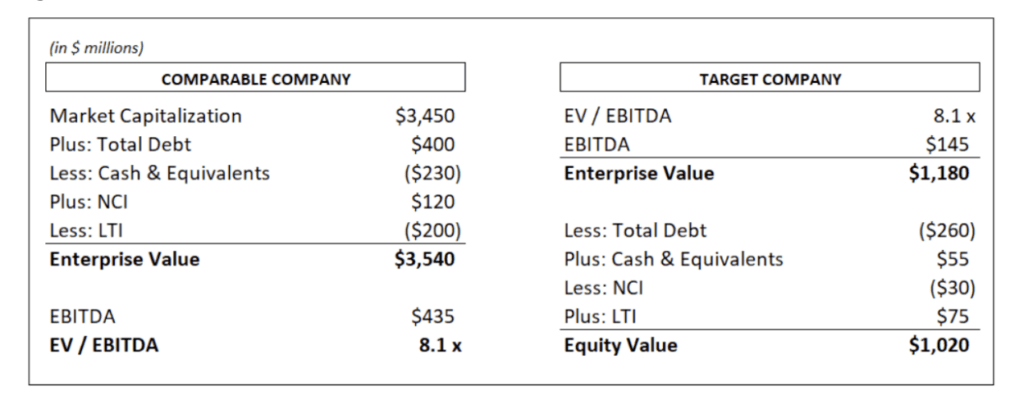

Figure ENTV17.1 below shows a simple example of deriving an EV / EBITDA multiple, and then using this multiple to calculate a target company’s Equity Value. We calculate the EV and the EV / EBITDA multiple of the comparable company by starting with equity value (i.e. market capitalization) and then making the required adjustments to arrive at the EV, which are the assets that generate the EBITDA. We then use the resulting multiple to estimate the EV of the target company, and make the reverse adjustments to arrive at the implied equity value of the target company:

Figure 1:

As mentioned earlier, where possible it is preferable to use market values for all the adjustments. Equity investors will attempt to place a market value on all the firm’s assets when pricing the stock, so when making adjustments, it is important to try to use the same basis.

What happens to a company’s enterprise value when it pays a dividend?

If a company issues a dividend, its enterprise value does not change. If a $100 mm dividend is issued to shareholders, the company’s equity value is reduced by $100 mm which makes the company’s enterprise value go down by $100 mm. However, the company’s cash will decrease by $100 mm which makes the enterprise value increase by $100 mm. This is because enterprise value is equity value, plus debt, less cash. The net effect of these movements is that the enterprise value is not changed when a company issues a dividend. The other way to think about this question is that since cash is not an operating asset, paying a dividend does not impact the EV (the value of the operating assets).

Paying a dividend is a financing decision. By paying a dividend, the company essentially becomes more levered, but the value of the underlying assets has not changed.