What is working capital?

The high level definition of working capital is simply: current assets minus current liabilities. The three most common working capital items are accounts receivable (asset), inventory (asset) and accounts payable (liability). These are balance sheet accounts that the company needs to run its business. For example, receivables are needed because companies need to extend payment terms to clients. Inventory is needed to have goods available for sale when a customer places an order. Movements in these accounts can have a big impact on cash flow, so they need to be carefully managed by the company to ensure there is sufficient cash to fund the movements in these items.

Users of financial statements need to understand the differences between accounting results and cash movements, and the resulting relationship between the income statement, cash flow statement and balance sheet.

It is important to note that the “change in working capital” used for the Operating Activities section of the cash flow statement includes only the non-interest bearing current assets and current liabilities. In other words, the change in working capital excludes cash & equivalents (asset) as well as short-term debt (liability). This is because the cash flow statement captures changes in these accounts in other ways – the change in cash is captured by the cash flow statement as a whole, and the change in short-term debt is captured in the Financing Activities section of the cash flow statement.

What is cash accounting?

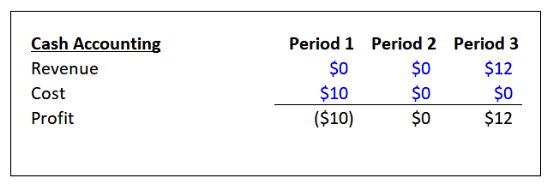

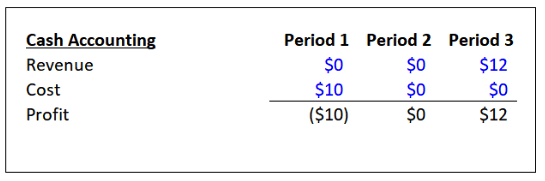

Cash accounting tracks the actual movements of cash in a company. Figure 1 below shows part of an income statement put together using cash accounting. If the company used $10 mm in cash to manufacture a product in Period 1, then these costs would be fully expended in Period 1 using cash accounting. The product may have been sold to a customer for $12 mm in Period 2, but the company did not collect a cash payment from that customer until Period 3. Using cash accounting, the revenue of $12 mm would be recorded in Period 3 since this is when the cash was actually collected.

FIGURE 1

The issue with cash accounting is that it does not provide an accurate measure of the “economic” performance of a business. In Figure 1, the company is shown as unprofitable in Period 1 and very profitable in Period 3. This does not provide investors with an accurate depiction of the company’s true profitability. Companies usually don’t demand cash payment upon delivery of products or services. Instead, companies often extend credit terms to their customers. For these reasons, cash accounting is not an effective way to measure the activities of most companies since it does not match sales and associated costs, which therefore means that it does not effectively measure a company’s profitability.

What is accrual accounting and why is it needed?

Accrual accounting provides a better measure than cash accounting of a company’s economic activity. In accrual accounting, revenue is allocated to the period in which it is earned, regardless of when the cash is collected. Costs are then matched to the revenues, regardless of when cash was paid in relation to those costs.

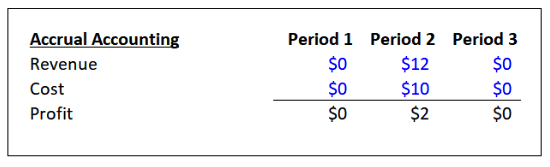

Figure 3 compares the accrual method of accounting with the cash method shown in Figure 2. Since the product was sold to a customer in Period 2 for $12mm, then the revenue is “accrued” to Period 2 since this is when it was earned. Then, the $10 mm in costs that are associated with this revenue are “matched” into Period 2 as well. As shown below, the company records $2 mm of profits in Period 2 and no profits in the other periods. This provides us with a better picture and measure of the activities and profitability of the business. The accrual system does not follow the actual flow of cash through the business. It effectively allocates or “accrues” revenue to the period in which it was earned and then “matches” the costs associated with this revenue into the same period.

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 3

How do the financial statements reconcile the difference between accrual accounting and cash flows?

Financial statements need to adhere to generally accepted accounting principles, which typically rely on accrual accounting as described above. However, the financials also need to reconcile to the net amount of cash a company generates or uses during a period – in other words the change in cash balance from period to period needs to be explained. This is where the cash flow statement comes in.

The cash flow statement must adjust the net income to reconcile it to the actual cash movements during the period. In other words, the cash flow statement will reconcile the income statement with the balance sheet. This will occur through the line in the operating activities section of the cash flow statement called “Change in working capital”.

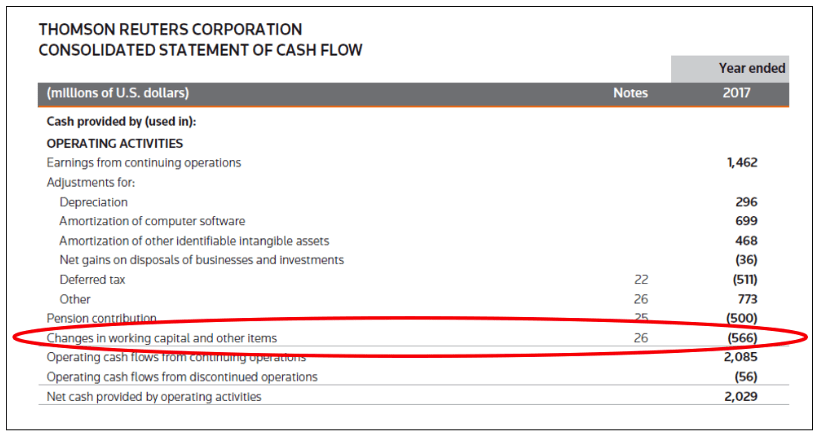

In Figure 4 below, note that the cash flow statement begins with “Earnings from continuing operations” which will come directly from the Income Statement and will reflect accrual accounting. To reconcile to actual cash flow, the operating activities section will make adjustments for non-cash items (such as depreciation, amortization and deferred taxes). The row labeled “Changes in working capital and other items” will adjust the earnings for any differences in reported revenues and costs versus actual cash movements.

FIGURE 4

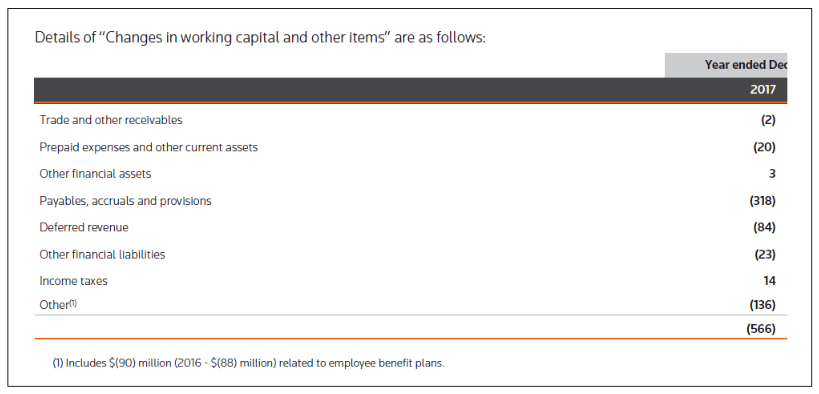

In the example above, the company’s reported earnings must be adjusted downward by $566 mm for working capital items in order to calculate operating cash flow. The reason for this may have included revenues recognized above what was received in cash (i.e. creation of accounts receivable) or a variety of other items. This line will show the net impact of changes in all the working capital accounts. Sometimes companies will break-out the movements in the individual accounts directly on the cash flow statement. In the case of Thomson Reuters, footnote 26 (see Figure 5) provides more detail:

FIGURE 5

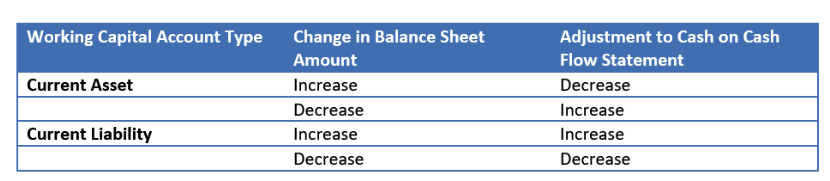

The general rule to remember with respect to working capital assets and liabilities, and their impact on the cash flow statement is as follows:

Should cash balances and short-term debt be included as working capital accounts?

By definition, since cash & equivalents are current assets and since short-term debt (including bank indebtedness and long-term debt due within one year) are current liabilities, they would be captured under the classic definition of working capital, or current assets less current liabilities. This is more of a liquidity measure that would be analyzed by lenders, or by a buyer of a company.

However, recall from an earlier question that the change in working capital for the cash flow statement includes only the non-interest bearing current assets and current liabilities. Since cash and debt are both interest bearing, they should not be included in the cash flow statement change.

The change in these interest-bearing accounts is NOT reflected in the cash flow statement line called “Change in working capital items”. The change in these balances is captured elsewhere on the cash flow statement. With respect to cash & equivalents, the cash flow statement itself calculates the change during the period and reconciles the beginning and ending cash balances found on the balance sheet. The change in short-term debt is captured in the Financing Activities section of the cash flow statement.

In other words, the operating activities section of the cash flow statement shows the change in non-interest-bearing current assets and liabilities. This is why the cash flow statement line is sometimes called “Changes in non-cash working capital items”.

What are some common working capital accounts?

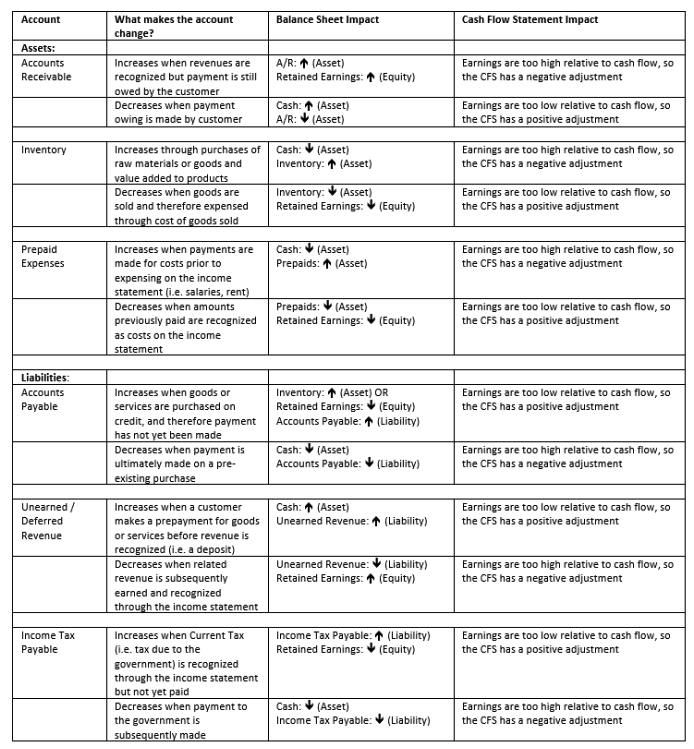

The table below lists some common working capital accounts and describes how they get created and impact the financial statements: